Mercury's Atmosphere

Gas in Mercury's atmosphere is so rarified that collisions between particles occur with negligible frequency. Like the atmospheres of Earth's Moon and Jupiter's moon, Europa, we refer to this very thin atmosphere as a surface-bound exosphere. It's an environment where the standard definitions of pressure and temperature do not apply. The composition of Mercury's atmosphere is similar to our Moon and it reflects the rocky surface material: calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, iron, aluminum, manganese, oxygen, as well as some elements that are brought in part from solar wind like hydrogen and helium. Photo-desorption, meteorite impacts, themal evaporation and sputtering are all processes that sustain a very thin atmosphere on this planet. The community has debated the relative importance of each process on the different atmospheric constituents for nearly 40 years; progress has been incremental with consensus being hard won. Many major advances in our understanding can be attributed to the MESSENGER mission which orbited from 2011 to 2015. Like all scientific leaps, the data from this spacecraft raised many new questions while resolving a few old ones. ESA and JAXA are in the partnering on mission called BepiColombo: two orbiters arriving in late 2024 with more advanced and sensitive measurement capabilities.

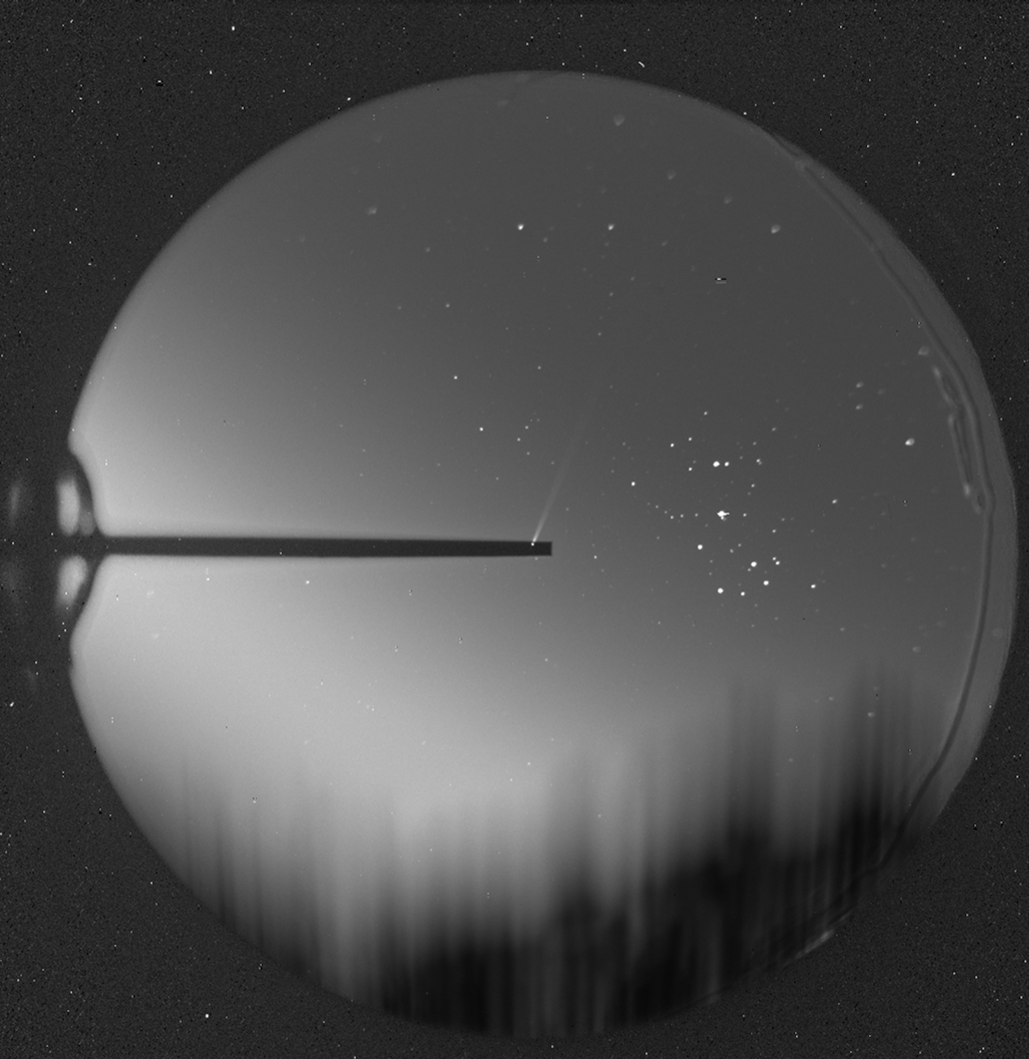

Sunlight blows Mercury's atmosphere into a comet-like tail. The tail is often mistaken as an effect of the solar wind, but it's mere sunlight; solar photons impart momentum when they scatter off the atoms and Mercury is very close to the sun. The photon scattering rate is particularly strong for alkali metals like sodium and potassium so these form the most distinct tail structures. Scattering depends on Mercury's Doppler shift and distance relative to the Sun, so the atmospheric escape rate strongly varies with season. Using a 10 cm coronagraph at McDonald Observatory, I've at times recorded the sodium atmosphere extending to distances of 2.5 million km, making it one of the largest structures in our solar system. The field of view above is 7 degrees of sky. Mercury is behind the black filter strip, the Pleiades are to the right, and trees on the horizon are smeared by tracking during this 6 minute exposure.

Below is a movie of Mercury's comet-like tail, which I've processed using 2 days of images from the HI-1 instrument on the Sun-orbiting STEREO-A spacecraft. The waves moving through the background are due to Thomson scattering of electrons in the solar wind. The tail shows characteristics common to sodium, although that prognosis is not yet definite. Mercury's tail points nearly along the line of sight, whereas these solar wind structures scatter preferentially perpendicular. This means that the planet is in the foreground and the solar wind is in the background, and so my 'white whale' of observing Mercury's atmosphere react to solar activity is not acheivable by this technique. Some scientists think the planet's atmosphere's largely static, with only seasonal variability. Others are confident the atmosphere exhibits large changes on hourly timescales due to it's interaction with the solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field. I'm somewhere in the middle, but I lean towards the latter more than most.

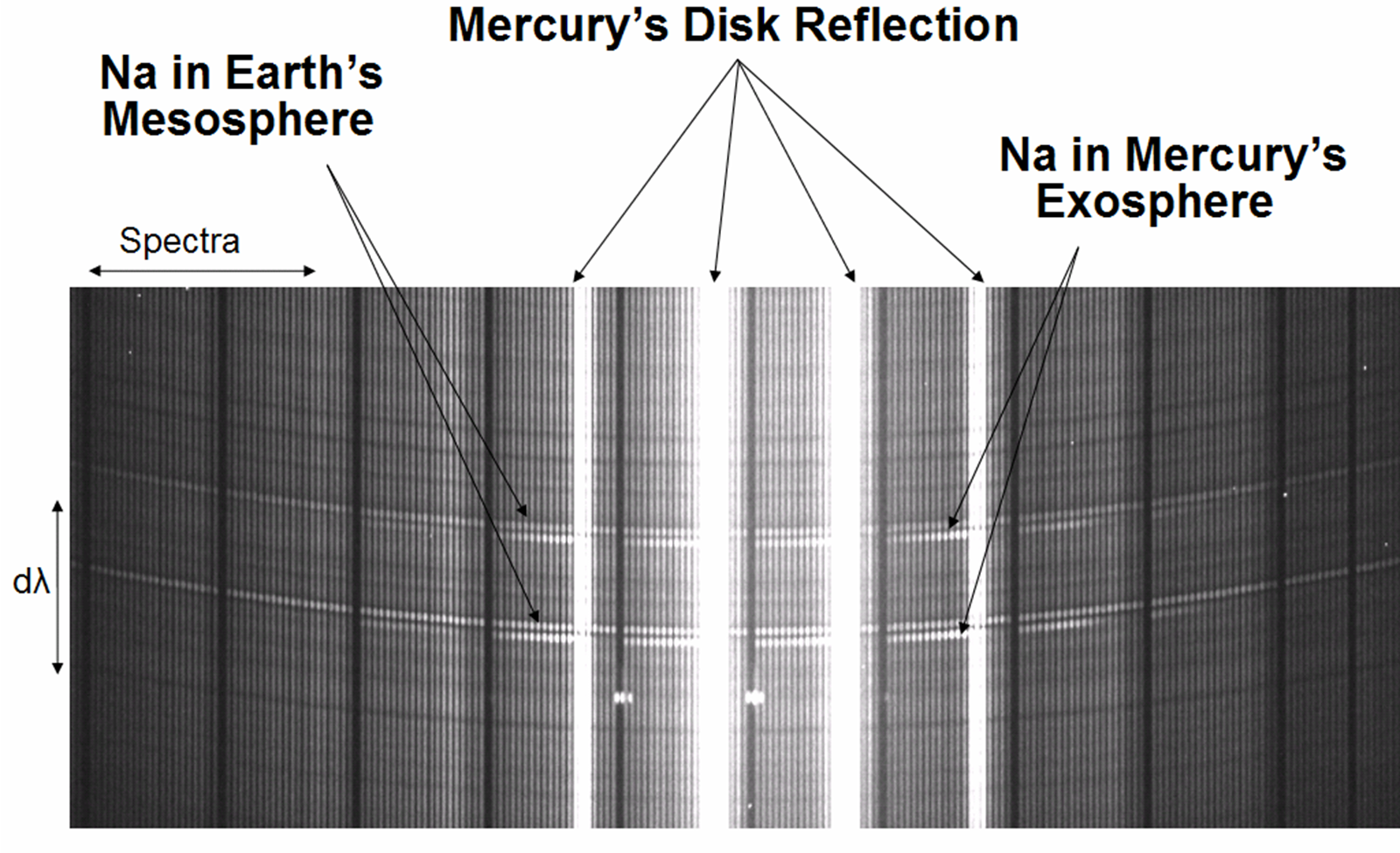

McDonald Observatory is also home to a small 40 cm telescope with a fiber-fed instrument. To the best of my knowledge, it's the world's only integral-field echelle spectrograph, designed by Jeff Baumgardner of Boston University. This instrument simultaneously records 246 high resolution spectra, but over only 4 nm of free spectral range, selectable with filters and grating tilts. Each spectrum is separated by 8 arcseconds on the sky, allowing an image to be reconstructed at a desired emission line. Optimizing the data reduction and calibration procedure is tricky and it's taken me several years to get it right. It works like this:

Resultant images like the bottom right show about 30% higher colum density in the northern lobe of Mercury's sodium tail on average. Why this asymmetry? Mercury's magnetosphere! It's magnetic field is not in the center of the planet, but about 500 km to the north. This allows the solar wind particles greater access to the southern surface. Normally when solar plasma hits a planet it causes things like aurorae. On Mercury, there's no substantial planetary atmosphere for solar ions to collide with, so they just smack into the surface. The working theory is that they damage the surface, breaking bonds and making defects in grains of the topmost couple hundred angstroms of soil. This "gardens" the surface, making it easier for ultra-violet sunlight to liberate fresh atoms into the atmosphere. Nerds like us call this ion-enhanced photon-stimulated desorption. It's more efficient in the southern hemisphere because the magnetosphere channels the Sun's particles to the poles and the southern magnetic field is a weaker, allowing more access to the surface here. Once sodium atoms are liberated into the atmosphere, they get pushed around by sunlight and gravity. In the right mixture, they can actually drift into the northern lobe of the tail. Here's a simulation I cooked up:

In April 2016, we measured asymmetries in Mercury's comet-like tail with the 3.5 meter telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. This led to the the first detection of a potassium tail, which shows a slightly broader distribution than sodium, and is also concentrated in the northern lobe, presumably due to the magnetosphere's influence. We've done some follow-up the the 4.3m Lowell Discovery Telescope, but opportunities to observe the potassium tail are few since we can only detect it in a narrow range of orbital longitudes where radiation pressure peaks. The measurements pretty much all show a lopsided sodium tail though, and 20-30% enhancements in the north are typical. North-south effects from the offset magnetosphere are hard to pull out of the MESSENGER data set because of its orbital geometry. However, the spacecraft's data does show some enhancements at certain planetary longitudes. Longitudinal structures in Mercury's Na atmosphere probably somehow relate to the 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, but modeler's still are trying to figure out just how.

On May 9, 2016, colleagues and I traveled to the National Solar Observatory just down the road from Apache Point. The IBIS and HSG instruments on the Dunn Solar Telescope measured absorption in Mercury's atmosphere as it transited between Earth and the Sun. The transit data tells us how lopsided the atmosphere is in each direction, north-south and dawn-dusk. The jet stream was right overhead so our seeing wasn't very good, for the tip-tilt correction. The Nov. 11 2019 solar transit was weathered-out at the Dunn, but we observed most of event with Germany's GREGOR Solar Telescope in Tenerife and preliminary analysis of the data seems very promising. During both transits, I can also say the adaptive optics data from FISS at Big Bear Solar Observatory are fantastic. We're writing up these results now, so I won't preview them, except to say the atmosphere's similar to Helmold Schleicher's 2004 transit measurement, but the new data have higher spatial, temporal and spectral resolution. With luck and careful data reduction, we may even see some variations in the atmosphere during the transits.

Most recently, our research group has been comissioning the Rapid Imaging Planetary Spectrograph. The instrument takes very fast data at video rates. The idea is that you can then throw away the blurry ones and keep the ~5% of images that have crisp structure when you were lucky enough to "freeze" out atmospheric seeing. The first light data below uses 1/20th of a second expsoure times. The spectrum shows Mercury's sodium emission shifted slightly from the solar absorption. By reconstructing an image from the spectra, we see the planet's atmosphere is concetrated at the poles. The southern pole is usually brighter, but it varies. Pretty much whenever planetary geometry allows, we're utilizing this new technique to measure sodium and potassium and better understand Mercury's atmosphere.

Updated 2020-02-28